Stop making fun of other people’s English. It’s not fun anymore and it doesn’t make you seem intelligent.

There. I said it. This isn’t news, but it’s a good reminder and I’ll tell you why.

I used to be a stuck up bitch about the English language and grammar. Like most of my friends whose line of work was in either media, PR, or marketing, I took pleasure in laughing at someone’s broken English and wrong pronunciations. Like most of my friends who shared my interest, I felt superior over others because I felt that I had above average communication skills.

This doesn’t come to me as a surprise because I spend most of my waking moments in a newsroom where zero tolerance for mistakes is practised. Journalism and print media production requires me to be apt, correct, and nitty-gritty about details.

I was a newspaper proofreader too. I have spent literally hundreds of nights on a desk with a red pen and the AP Stylebook next to me.

“You are in the business of making things perfect!” my editor reminded me.

Any mistake that goes beyond my walls of judgement are bound to be cringed at. Or scratched by red ink.

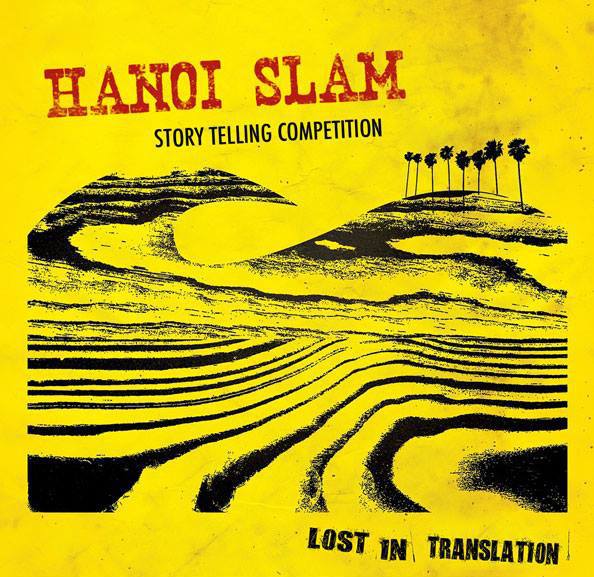

Fast forward to today: I’m in Vietnam and massacred English sentences are everywhere.

Do I freak out and draw my red pen to wage war against typos and word misuse?

No.

I have grown to become tolerant towards wrong English. But that doesn’t mean that my communication standards have deteriorated in quality. It only means that I am making a bigger room for improvement and learning.

And I think that anyone who thinks that they are educated should do the same.

English language penetration in some cities in the ASEAN region are relatively low. But I don’t think that should hinder anyone from being productive and from expressing themselves.

In 2011, I have been to a media camp in Thailand where I’ve seen my fellows from Cambodia, Thailand, Singapore, Myanmar, and Vietnam engage in oral debates, gracefully discussing media, law, lifestyle, and human rights. They didn’t speak fluent American English but they were able to clearly express ideas that none of us would have ever heard of had they not been given opportunities to speak.

Earlier this year, I met a throng of professionals in FK Norway’s prep course (where my journalism exchange is listed as one of the projects in the program). There were nurses, doctors, social workers, human rights advocates, artisans, and agriculture experts; not everyone could speak fluent English. But I didn’t find that bothersome at all.

The truth is that language barriers are not strong enough to prevent anyone from sharing good knowledge.

Today, I now cringe at how some of my friends back in the Philippines make fun of people who don’t have perfect English. They don’t seem smart at all; they appear condescending and devoid of social grace.

Correcting other people’s English isn’t a new idea. Maybe the Vietnamese, who perhaps don’t speak perfect English, have something better to say.